Czekalska + Golec

Newborns

May 29 – July 25, 2020

At whose cost do we live? At whose cost do we cultivate art? Who has had to donate their skin, bones and life for the sake of culture? Tatiana Czekalska and Leszek Golec do not pose these questions in the context of the exploitation of man by man. Interpersonal exploitation is only the tip of the interspecies pyramid of abuse, which provides the basis for our faith, hope, and love – especially self-love.

The Czekalska and Golec exhibition comprises a collection of artifacts made from recyclable waste. This artistic recycling has as its subject material evidence of the religious cult: devotional items, liturgical vestments, theological books. The practice of recycling is not only a manifestation of the artists’ ecological attitude but also a mechanism for revising the values which underlie our culture. The revision consists in encouraging spectators to look at these foundations from another perspective – to leave the anthropocentric universe and adopt the point of view of the creatures whom we have placed outside its boundaries. Consequently, we are looking through the eyes of elephants, dogs, calves, moths, bivalves, spiders, and maggots.

In the shadow of the climatic crisis, the artistic work of Czekalska and Golec seems to be part of the ecological turn, which has been present in the world of art for several years. You can also say otherwise: it is a social consciousness that is now becoming part of the discourse which the artists had taken up long before the spectre of the catastrophe forced us to critically consider the relationships between the human and the non-human. Tatiana Czekalska and Leszek Golec, a couple both in life and art, have expressed the posthumanist attitude since the beginning of their cooperation in 1996. However, who wanted to discuss posthumanism in the 1990s, two decades before the term “Anthropocene” became a popular hashtag and entered colloquial speech? Czekalska and Golec created works from cat fur, staged exhibitions with the participation of cats and for cats, as well as sheep and fruit flies, and made sculptures for spiders. Today their field of interest is close to the center of the discussion. In the past, it used to remain on the margins of public debate. It was not the art of Golec and Czekalska that changed, but the world; the artists have consistently held the same positions for years. Their attitude has not been shaped in reaction to the prophecy about a disaster, but it has always been ethical.

Current ecological and posthumanist narrations are often articulated in a tone which resonates with religious discourse. In this approach, the looming ecological disaster, the melting of icebergs, whose water will deluge the human universe like the Flood, antediluvian viruses released from permafrost, draughts, downpours and hurricanes are plagues which will strike humankind as punishments for its offences against nature. If there is still any hope for salvation, it lies in collective contrition, penance and asceticism, renunciation of plastic bags and disposable straws, the practice of rituals of rubbish segregation, and the observance of strict fasting, especially as regards products of animal origin.

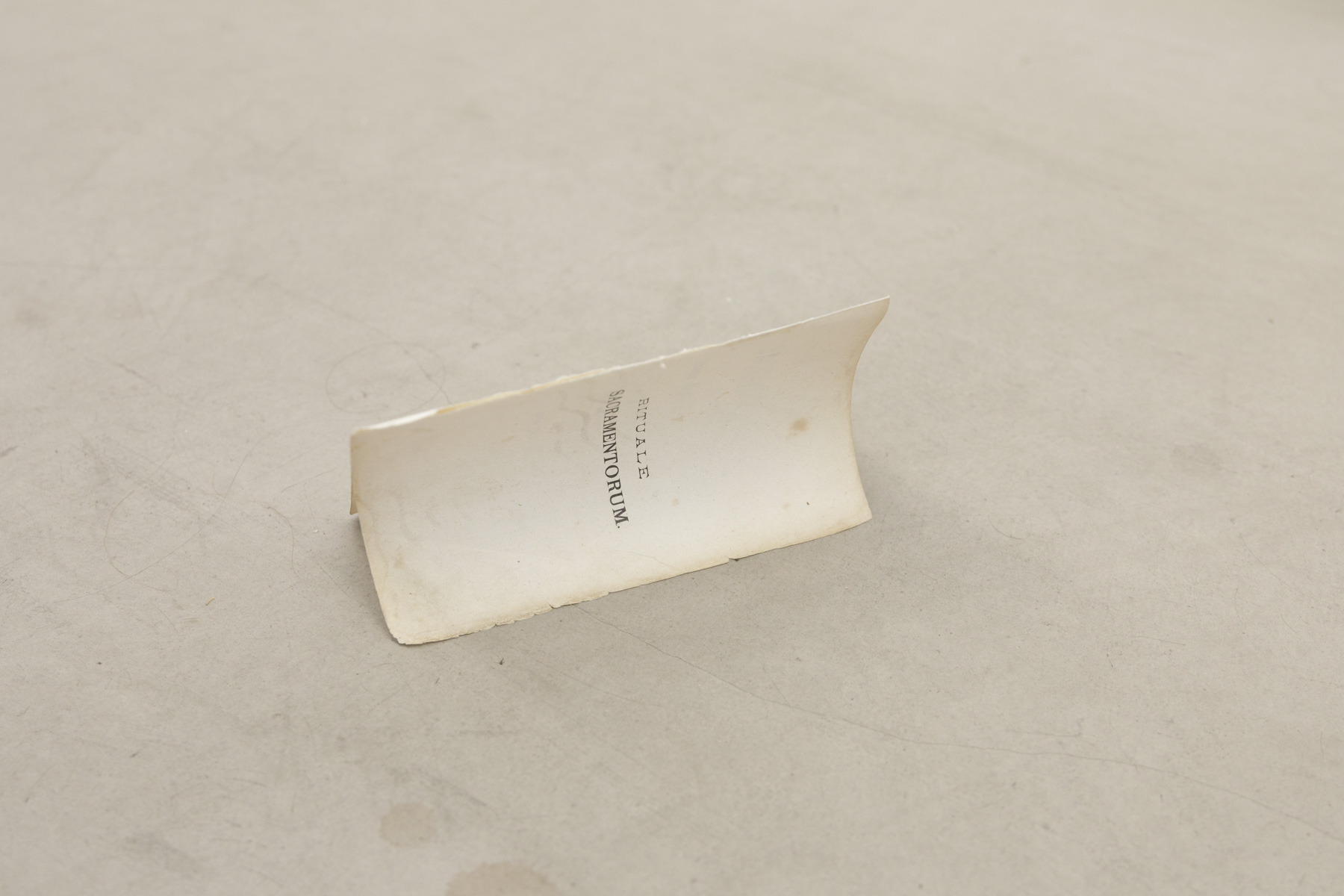

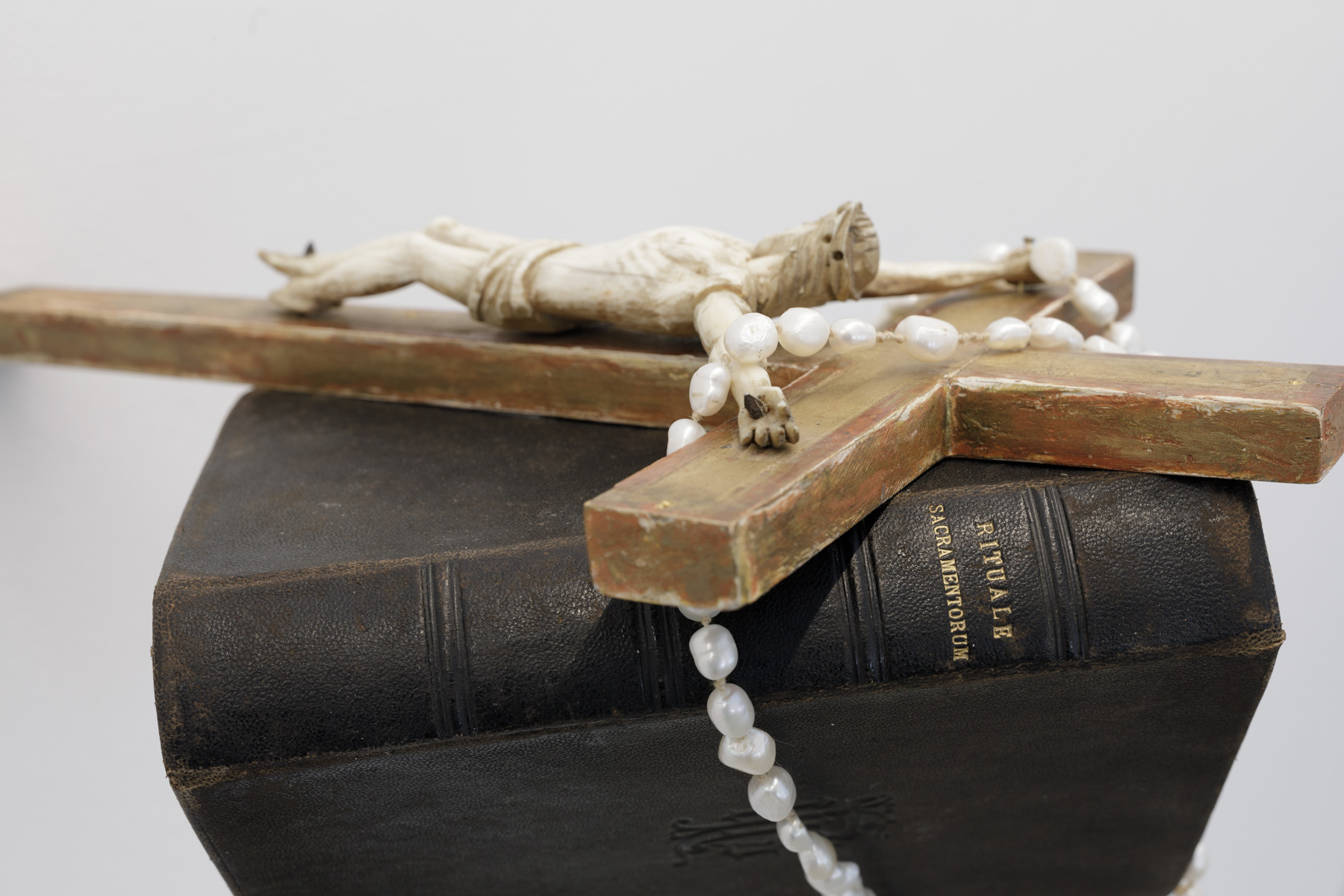

The need to limit consumption and wasteful exploitation of the planet’s resources is obvious, but Czekalska and Golec arrive in their deliberations at some other point, going one step further. They make an inspiring reversal of notions. Instead of exploring the religious dimension of ecology, they take a look at the posthumanist dimension of religion. They focus on its artifacts. They show us sacred books, not for another reading, but so as we can touch – at least in thoughts – a book cover made of the skin torn off the groin of a calf, a six-month- old cow’s child; it is difficult to imagine material which would be more delicate to touch. Bringing a rosary to the exhibition, the artists count cultured pearls and thus mussels which “devoted themselves” to making this devotional object. Pearl rosary beads lead to a crucifix, carved in ivory; here is the representation of the sacrifice engraved on the body of another offering. Used Catholic liturgical vestments are presented as moth food. Czekalska and Golec pour (vegetarian) feed for domestic animals, and invite fruit flies to the exhibition, so that they can participate in the feast of a paradise apple. The artists are interested in palimpsests, gouged in the pages of holy texts by insects. Holy pictures and theological volumes, on the other hand, are used as shelves and plinths, supporting artifacts which serve to protect any life in its most modest manifestations.

Stach Szabłowski