Gabriele Stötzer

I come from a country that no longer exists

September 30 – November 27, 2021

She created performance without knowing the word. She created feminist art without knowing what it was. She created works which are today compared by art historians to the works of Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke, Nancy Spero, Carolee Schneemann and VALIE EXPORT, but she had not heard of these artists yet. Galeria Monopol is hosting the first ever solo exhibition in Poland of the German visual artist, writer, political and social activist – Gabriele Stötzer.

“I come from a country that no longer exists”, says Gabriele Stötzer often, an artist who in the 1980s belonged to the progressive underground scene of the former German Democratic Republic. She made friends with young punks, was a member of the squat scene, did photo sessions and performances, shot subversive experimental films, as well as worked in textiles, ceramics and fashion design. She said and wrote what she thought: plainly. Quite a lot for someone who knew that everything she was doing was illegal and that she was a Stasi target.

It all started in 1976 with the famous wave of protests against stripping the singer Wolf Biermann, whose lyrics harshly criticised the regime, of citizenship. Gabriele signed a petition in his defence and it was this signature that cost her a year in prison, which changed her life. After regaining her freedom, she began to create. While all political prisoners wanted to be “removed” to the West, Gabriele wanted to stay. She ran an alternative, and therefore at the same time illegal, gallery “Im Flur” [In the corridor], made contacts and set up illegal art groups. Once again, this was not to the liking of the authorities: the gallery was quickly closed down, and secret proceedings were initiated against Stötzer in order to “make her harmless” again: this time for a longer period. To achieve this goal, her artistic activities had to be subsumed under some provision of the penal code. The last sentence in the document from the secret trial bearing the venomous code name “Toxin” (ah, how she must have got on their nerves!) reads: “The purpose… is to develop evidence under section 106 of the Penal Code” (anti-state smear campaign). When Gabriele meets a young transvestite who will pose as a model for her, she doesn’t yet know that the boy is a trap set by the Stasi. She takes a series of great cross-dressing photographs of him, but she knows exactly what boundary she cannot cross in order not to endanger either herself or him. “In none of the photos does the boy have an erection, so I could not be accused of pornography. They really wanted to put me back in jail, but this time they couldn’t find any dirt on me”, she recalls. It is only after the reunification of Germany that she finds out that their acquaintance was arranged by the authorities.

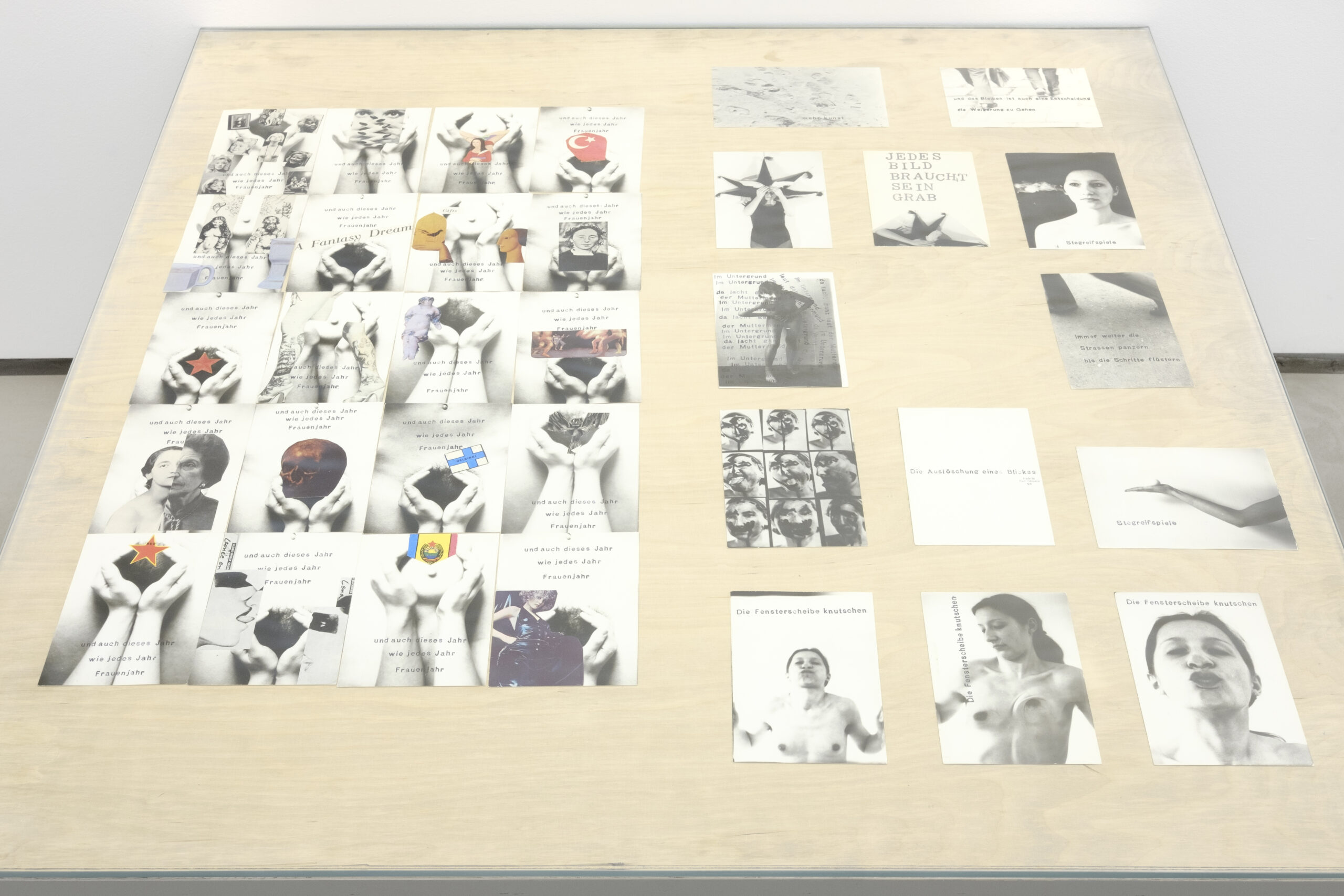

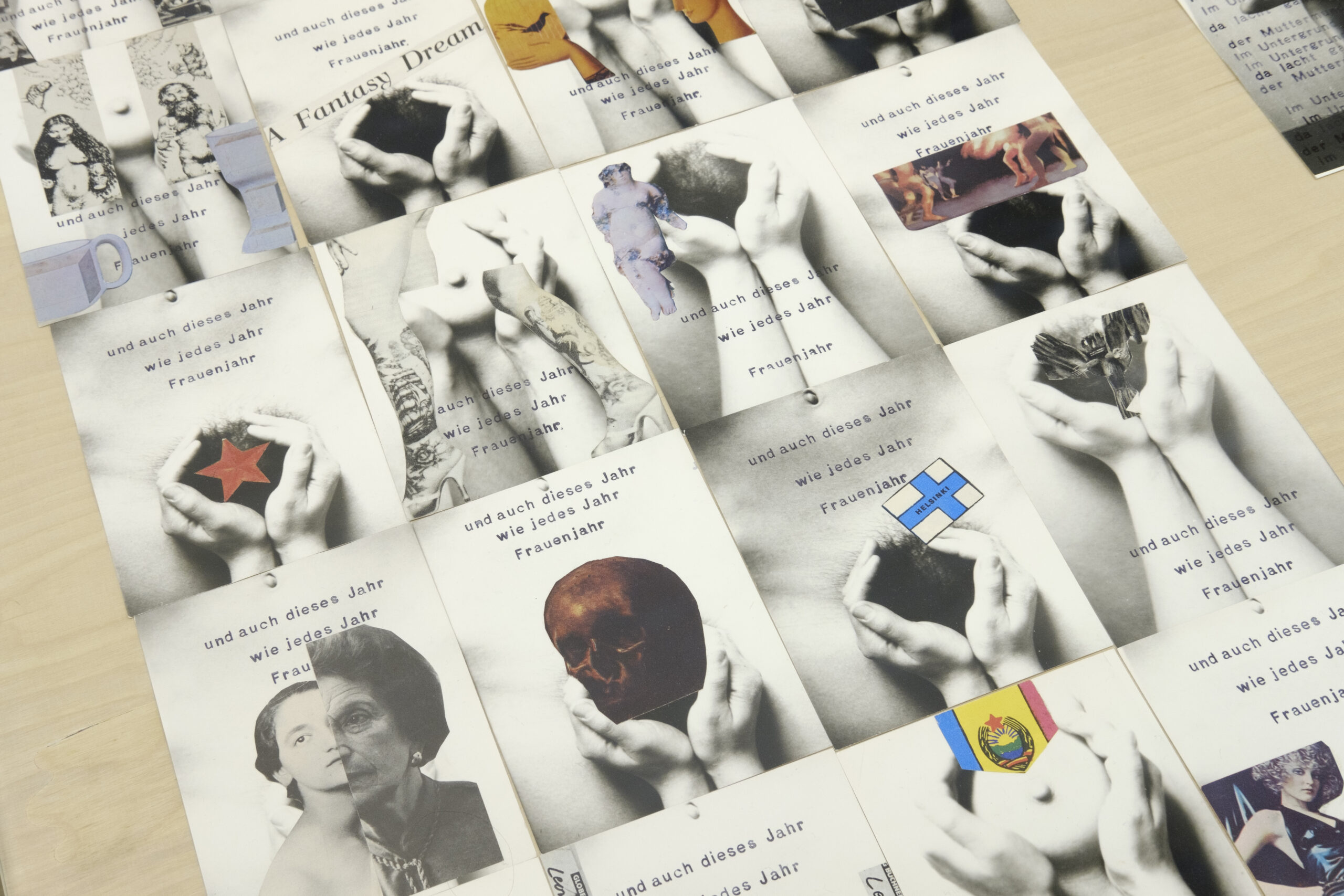

Although Gabriele knows nothing about Mail Art, she uses the best method available to distribute her work: the post. She sends photographs of her performances, inscribed with a stamp, to her friends as postcards. One of the pictures shows hands clasping a breast: “Also this year, like every other year, is the year of women”; another bears the following inscriptions: “The pill is for emancipation and gonorrhoea is against” or “If being a lesbian means sleeping with women, then all men are lesbians and women are homosexual”. With her works, Stötzer fought against the dominant image and role of women in the GDR. She was not aware that she was making feminist art, she was only aware of the importance of women’s solidarity to survive, something she learned in her cell with 22 other female prisoners. “I never did women’s art or feminism just because it was fashionable. What I did was existential for me, it was a form of survival. It was simply art”, says Stötzer.

However, unlike in other Eastern Bloc countries, the independent artistic milieu in the GDR was almost completely isolated from information about the art of Europe (both western and eastern) and the rest of the world. Stötzer was guided by pure intuition. Although not familiar with terms such as process art, participatory practices, or social sculpture, she was most interested in artistic practice based on collaboration with others. From a political point of view, however, any group activity, such as running an underground gallery or establishing art groups, was particularly suspicious. Nevertheless, Stötzer founded the only East German female art group EXTERRA XX, named after the symbol of the female chromosome. Later, a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the group merged with other organisations and turned into the social initiative “Women for Change”. Women Power had some real political influence at the time: in December 1989, five of its members – including Stötzer – violently broke into the headquarters of the security service in Erfurt and stopped the mass destruction of Stasi files by its former collaborators.

In the public consciousness, the artist mainly existed as a social activist (she has recently been awarded the Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany by President Joachim Gauck for her political activities). Besides, she was associated more with literary than artistic circles, having published books like Zügel los [Reins Loose] (1989), Die bröckelnde Festung [The crumbling fortress] (2002) and others. There was never a good time for her art: either too early or too late; Stötzer was always pigeon-holed somehow out of place. Until 1989, her art was illegal, and after the Wall came down, art from East Germany was no longer interesting; everyone wanted to forget this chapter of history. That’s when she found out that she was a feminist, but feminism at that time was still of no interest to anyone. Once she was allowed to exhibit publicly, she was told that it was better for her to stay in the underground, because underground art would no longer be honest in legal circumstances. We had to wait for major group exhibitions like Re:act Feminism (Academy of Arts in Berlin, 2008 and Wyspa Art Institute in Gdańsk, 2012) or Gender Check (MUMOK in Vienna, 2009 and Zachęta – National Gallery of Art in Warsaw, 2010). Since then, Gabriele Stötzer has also been perceived as a visual artist. The process, initiated a decade ago, of rediscovering the work of radical female artists from the former GDR, whose output was deliberately and systematically pushed out of consciousness and out of art history, is still ongoing and perhaps now the moment for revision and recognition has finally come. Alongside an exhibition such as The Medea Insurrection: Radical Women Artists Behind the Iron Curtain in Dresden (2018), Gabriele Stötzer’s work and vast archive has been recently shown by the Leipzig Museum of Contemporary Art, while Berlinale 2020 featured her Super 8 films.

The exhibition at the Galeria Monopol focuses on those aspects of Stötzer’s output which, despite the lack of direct contact, bears surprising similarity to the work of many Polish avant-garde artists of the 1970s and 1980s. The struggle against the totalitarian regime along with the historical and social circumstances in which her works were created explain why a Polish audience understands her art intuitively, without the need for detailed clarification. Moreover, it is not only the historical context, but also current social themes, such as the movement for the rights of the LGBTQIAP+ community and women, that make Gabriele Stötzer’s art relevant and fresh again. The exhibition includes photography, performance documentation, video and textiles.

Monika Branicka